Heavy Weather Sailing

“Astonishingly well behaved in strong winds, so much so that they don’t even bother with reef points anymore. No one was using then anyway"

The Melonseed has a reputation for sailing capably in heavy weather. Most Melonseed owners would be willing to share a story or two about an adventure in strong winds, and how well their boat handled.

Let’s take a very basic look at the factors that all combine and contribute to this performance feature.

To make it simple, let’s start with the idea that every boat ever designed is basically a bubble of air, as air is the one of the most buoyant things on the planet. Whether the bubble of air (the boat) is wrapped in wood, fiberglass, metal, etc., it doesn’t matter, the basic idea is to displace water and fill the cavity with air because air loves to float! The shape of the bubble or in fact the ultimate design of the boat that is created by the yacht designer or naval architect is what allows the boat to perform certain tasks better than others. Think of several different kinds of boats (sailboats, tugboats, aircraft carriers, kayaks, etc.) and you can visualize the multitude of different shapes of boats there are, and what their jobs are. All the bubbles are different.

Now, take your mind back to the mid to late 1800's and imagine that you are designing a small work boat that has to be capable of handling a wide variety of wind and wave conditions, year 'round -- from flat summer calms to the heavy winds and choppy waters of winter. These are quite different functional demands from the design criteria of the modern daysailer that is apt to sail mostly in optimal conditions. For function beyond that window of fair weather, the daysailer needs to be set up with reef points to minimize sail area in strong wind and an outboard motor when the wind is light or non-existent.

So what did an unknown brilliant nineteenth century waterman/boat builder from Barnegat Bay do with the design of the hull if he wanted it to be exceptionally stable and not heel under the force of strong winds? He shaped the bubble so that a large percentage of the overall volume of buoyancy in the boat would be amidships and offset as far outboard as possible so that this buoyancy would keep the boat from being forced down and overcome by the pressure of the wind on the sail.

Imagine hanging on to a basketball while you are in a swimming pool. You would find that the cubic foot of air in the ball will probably float you. Well, there are lots of cubic feet of air in the full buoyant midsection of the MS, and that air really resists being depressed down!

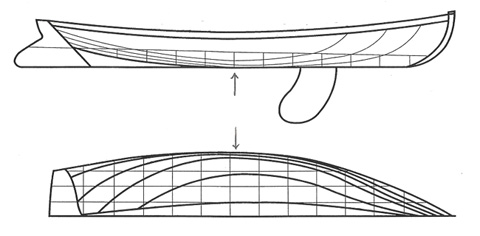

If you look below you will see the lines drawings of what is widely known as the “Chapelle” Melonseed, the boat seen on page 209 in Howard Chapelle’s famous book American Small Sailing Craft. This is arguably considered the standard by which all Melonseeds are compared, and which the CRAWFORD MELONSEED SKIFF is nearly identical to. Chapelle commented as follows in his description of the boat: “to produce a more seaworthy and drier boat for use in the choppy waters”, and “was intended for use in open water”.

Note where the arrows are pointing. This is that big buoyant midsection that is very hard to force down under water.

Looking at the two photos below you can see what this looks like on the hull and just how well this large area of buoyancy helps keep the boat from heeling excessively.

The Melonseed seems to heel over just so far and then locks up and gets extremely stable and difficult to tip over further. You get very comfortable in the Melonseed as you soon learn that with proper handling of the sheet and tiller that a capsize is quite unlikely. Also worth noting is that at no point in this process of heeling over under the force of the wind is the boat unusually tender and jerky, and all movements are easy and somewhat predictable.

Further evidence of this is seen in the two photos below. You will note that in both examples that the boat is heeled about the same, the waterline, the angle of the boat into the wind, and the trim of the sail are pretty much all the same.

The photo on the left was taken in what might generally be considered nice enjoyable sailing conditions, probably 12 knots. The photo on the right was taken in Plymouth (MA) Harbor in winds that the National Weather Service recorded at 25 MPH! That’s approaching DOUBLE the wind strength! The Melonseed has settled down on the buoyancy and continues holding the boat upright regardless of the force of wind.

Here’s some more of the same, showing the skippers comfortably in control with their boats considerably heeled over:

Doing what good sailboats do, the Melonseed handles the force of the wind and drives forward, accelerating, getting more lift from increased speed across the surface of the water and therefore even little more stability. The photo below shows an example of this.

Now that we understand what the hull does, let’s take a look at the sail rig on the CRAWFORD MELONSEED SKIFF.

The Melonseed carries a remarkably simple and efficient traditional sail rig called a SPRIT RIG. Sprit rigs have been used for centuries on workboats of all sizes. The rig gets its name from the simple pole that forces the peak of the sail up, and that pole is called a “sprit”. Incidentally, the boom on the Melonseed is a “sprit” boom because of the similar way it is rigged to the mast and sail. The sprit rig is a “quadrilateral” or four sided sail of modest size, only 62 square feet.

Every sail has a geometric center called the “center of effort” or CE, and this can be thought of as the spot on the sail where the wind force is centered. The higher the CE is on a sail, the more leverage the wind has to force the boat over. If you take the same square footage of sail area and make it into a modern triangular sail, the CE will be much higher up over the boat than the CE on the quadrilateral sail and have more power to force the boat over. In other words the sprit rig generates less heeling force for the same wind strength.

Like many of the other traditional quadrilateral rigs such as the gaff and lug, sprit rigs are quite graceful and set in a beautiful picturesque shape with the peak of the sail well forward of the clew and a lovely flowing curve on the trailing edge or leech of the sail. The harder the wind blows on a sprit sail, the more the peak is forced forward and this is called “twist”. While this is a lovely sight, it is also allows a very interesting thing to happen. As the increased wind pressure forces the boat over more and the twist increases, this sets the sail in a position to allow some of the wind to slip right off the top of the sail and reduce its force on the sail. You now have a sail that in a way is almost self reefing! The harder the wind blows, the more some of it slides off the sail. Additionally, because the top of the sail is now not able to hold the force of the wind and the lower part of the sail is doing most of the work, the CE has now shifted down lower on the sail area and exerting LESS force on the mast than before and therefore less heeling moment on the boat.

The photo below shows the Melonseed in exactly this circumstance. Observe the shape of the sail and all that is described above. You can see the sail doing exactly what is described above and that the boat is sailing merrily along in a strong breeze.

++ ADD IT ALL UP! ++

1. The buoyant hull is hard to force over.

2. The sail shape causes less heeling force than most boats.

3. The twist in the shape of the sail eases the wind force in a gust.

4. The boat accelerates generating lift and even more stability.

What a remarkable combination of circumstances. All the above worked together to create a small boat capable of taking a hard working duck hunter out year ‘round on the Delaware Bay in the challenges of open water and heavy winds during an era when man and boat had to be able to survive when the option of calling the Coast Guard, Harbormaster or “911” was NOT an option.

The seas and winds have not changed in millenniums….and the Crawford Melonseed, much like its 19th century ancestors, when properly handled, is able to handle pretty tough conditions.

Let us acknowledge that all your sailing is unlikely to be in 25 knot winds, and hopefully you’ll mostly sail in those ideal weather days that we all dream of. However, it is comforting to know that if you are sailing a CRAWFORD MELONSEED SKIFF that when you encounter heavy weather you’ll be aboard one of the most capable small boats available.

Ultimately, all boats are at the mercy of the unpredictable forces of nature, and as stable as it is, the Melonseed is no exception being overcome. In the unlikely event that the cockpit is filled with water, there is positive flotation built into the boat.

Novice sailors who learn to sail in a Melonseed seem to become capable sailors very quickly. Learning to sail in many of the less stable small boats available today or commonly used in sailing programs, is often more about learning not to tip over rather than actually learning the skills of sailing the boat. Not so in the Melonseed. You quickly become confident in the boat’s stability and are free to focus on the handling of the sheet and tiller, and sensing what the wind and boat are doing. The learning curve on a Melonseed is very sharp.

With a little practice, experience, and prudent seamanship you will soon be comfortable in the Melonseed in strong winds.

While the Melonseed was designed to sail better in heavy weather than its contemporaries of the same era, it also testimony to the genius of the unknown designer of the boat that it will sail beautifully in medium air, light air and row as well as a true pulling boat in NO air. The shape of the hull of this boat is stunning and it goes effortlessly through the water in any sea condition, not just heavy wind.

In 1999, the esteemed naval architect Robert Perry reviewed the Melonseed in an article in SAILING MAGAZINE and said the following:

“I'll tell you what makes this boat special. It is as shapely a little hooker as you will find anywhere. From its hollow entry to its almost heart-shaped transom, this boat is a symphony of shapes. The sheerline is bold and sprung with confidence. Freeboard is minimal. The sectional shape shows a firm turn to the bilge, ensuring excellent stability and a forgiving nature.”

Nathaniel Herreshoff said “Water hates to be surprised”, and when you look at the Melonseed’s hull you’ll see the physical definition of that. The beautiful hull is a perfect example of “If it looks good, it is good”.

Maybe the simplest way to sum this all up is to say that no matter what the wind and sea conditions, this boat just loves to sail!

We’ll conclude this presentation with a copy of a letter received from Roger Rodibaugh of Lafayette, Indiana in which he described a sail in his beloved Melonseed Skiff “Nancy Lee”, followed by a Yahoo posting from Tom Downing sailing "Simple Gifts".

Greetings from blustery central Indiana.

I had a rollicking Holiday sail today in SW breezes that started out 15-20, gusting 25, and built up to 30, gusting 38 (the latter confirmed by Eagle Creek Airpark adjacent to the lake). It was a "double-tie-your-hat-on-day" with wall-to-wall whitecaps and one of those few occasions I was wishing for the ballast of another body, not to mention for protection from the spray. There were a number of larger sloops (20-26 footers) sailing with reefed main only, a Force 5, Laser, Sunfish and little ol' me and Nancy Lee. After a couple hours of sailing on all points, the last leg of the day was a broad reach -- and that was when it was gusting well over 30. Now that was something! You've all been there, so I'll spare you the prose -- just to say that there were some times in the bigger gusts that it felt like NL was about to break free and fly!

What a day and what a treat to be on the water in such a simple, pure, little boat who willingly handles more weather than I care to.

Cheers,

RJR

I like sailing in snotty weather, and that includes in my Melonseed. I've sailed in winds of 20-25 knots on both Long Island Sound and the Chesapeake, with the chop running to 3 feet (tops of chop starting to obscure the horizon).

The ride can get uncomfortable and wet, especially on the wind. Keeping pointing high in certain chop can be tricky, and you will bang about a bit. Oddly, this is harder in 2 foot chop than three - probably something to do with the relationship of distance between crests and the length of the boat. It will never be so wet that bailing is anything other than now and again. Only very, very rarely will blue water make down the foredeck and over the combing, and then not much. I've never had solid water come over the gunnel.

On the other hand, running can be exhilarating! I've spent hours beating out from the channel and down the harbor into the teeth of 20 knots, just for the pleasure of surfing home again. Back and forth, back and forth....

The sprit rig is a natural for gusty winds, the peak twists off to leeward in the gusts. See the article on heavy weather sailing on Roger Crawford's site.

I have never felt anxious in these conditions, but I did work up to them.

I've bought and sold bigger keelboats, I'll probably be buried in my Melonseed.

Tom Downing

'Simple Gifts'